Property Taxes and Budgetary Independence in North Dakota

Published October 2024; Link to Revised Draft

In general, a state policy that limits the extent of taxation can attract individuals and businesses to that state. Restrictions on fiscal expansion also limit the extent of the size of deficits and overall net indebtedness of the state. If parties are sensitive to the increased marginal costs due to wealth extraction and intervention, they may produce less. Or they may leave the state if that is a feasible option. More taxes will lead to less productivity in the long-run. Low levels of spending, on the other hand, limit the extent of indebtedness, making policymakers within a state more able to shape policy in light of promoting a healthy business environment and the welfare of citizens.

Following this logic, it is quite easy to begin to think in aggregates and ignore the details that drive these changes. While there is nothing wrong, per se, about this logic, the devil is in the details. Tax reductions can take a variety of forms as there exist many kinds of taxes. Some taxes are more disruptive of productivity, others less. Although a graduated income tax schedule might seem fair to those who face the barbs of poverty on a daily basis, such a tax system also discourages productivity. Likewise, corporate income taxes might seem like a convenient source of revenue from institutions that that hold a large proportion of the nation's wealth, high state level income taxes discourage businesses from setting up business in the state that adopts this policy.

Some states have relatively limited property taxes. However, identifying a state as having low property taxes is a somewhat complicated question. Property taxes tend to be collected by local governments rather than by state governments. As a result, we can only estimate an effective property tax rate that compares the aggregate value of taxes collected within a state to the aggregate value of properties across the state. During 2022, the effective rate of taxation for property taxes paid on an owner-occupied home in North Dakota was 0.97%. Compare this to New Jersey, the state with the highest rate (2.08%) and Hawaii, the state with the lowest rate (0.26%) Tax Foundation. Further, county level, within-state variation of property tax rates can be quite high, as indicated by the county level data provided by the Tax Foundation.

Tradeoffs for Property Tax Revenues¶

If local governments do not collect property taxes, then there are three possible consequences.

The fall in property tax revenues are offset by another form of taxation.

The fall in property tax revenues increase deficits of local governments.

The fall in property taxes are offset by transfers from the state government.

Local governments face significant intergovernmental competition and, as a result, this limits the ability of most local governments to increase taxes. Most citizens are willing to suffer a limited amount of taxation. However, as this burden increases they may seek to engage in business in neighboring counties, or even move away from the county in question if taxation becomes to burdensome.

Counties containing or close to a city center or, say, the state capital, will tend to have greater ability to levy burdensome taxes, including high rates of property taxation. Thus, we see property tax rates in highly populated counties near major metropolitan centers. Counties near Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles, San Diego, New York City, Austin, and Dallas, to name a notable but incomplete set of urban centers, are all subject to high property tax rates. We tend to observe low property tax rates in more rural areas. Of course, we may find exceptions to this trend, but in general it holds. (We invite you to take a close look at other major metropolitan areas.)

Intergovernmental competition makes property taxes an attractive source of funds for local governments. Property taxes are costly to avoid as this requires the sale of property by the owner. And of course, someone else will acquire the property, maintaining this source of revenue even in the case that property values fall modestly due to a decrease in demand. Given the incentives facing tax collectors and taxpayers, it should be no surprise that a significant portion of local government revenues are derived from property taxes.

There is also a moral case for property taxes. As economic activity improves, assets that platy a fundamental role in that activity naturally increase in value. Part of this moral case includes one's ability to avoid excessive taxation by simply incurring the costs of leaving the political domain engaged in extraction. Further, land is immovable and, therefore, straightforward to monitor and tax compared to other forms of capital. Owners benefit from increased valuations that may or may not be owing to their own productive activity. So long as property taxes are collected locally, owners will tend to have significant influence over the use of these revenues, thereby ensuring that property taxes are not pure losses or pure transfers. In the case of local collection, land taxes are a source of local sovereignty.

Concerning actual property taxes, we reference data aggregated at the state level between 2005 and 2021, property taxes and special assessments make up anywhere between 9% and 64% of local revenues within any single state. In general there seems to be a negative correlation between deficits of local government within a state and the extent of property taxes. This is especially true in states where the proportion of local revenues generated from property taxes is relatively large.

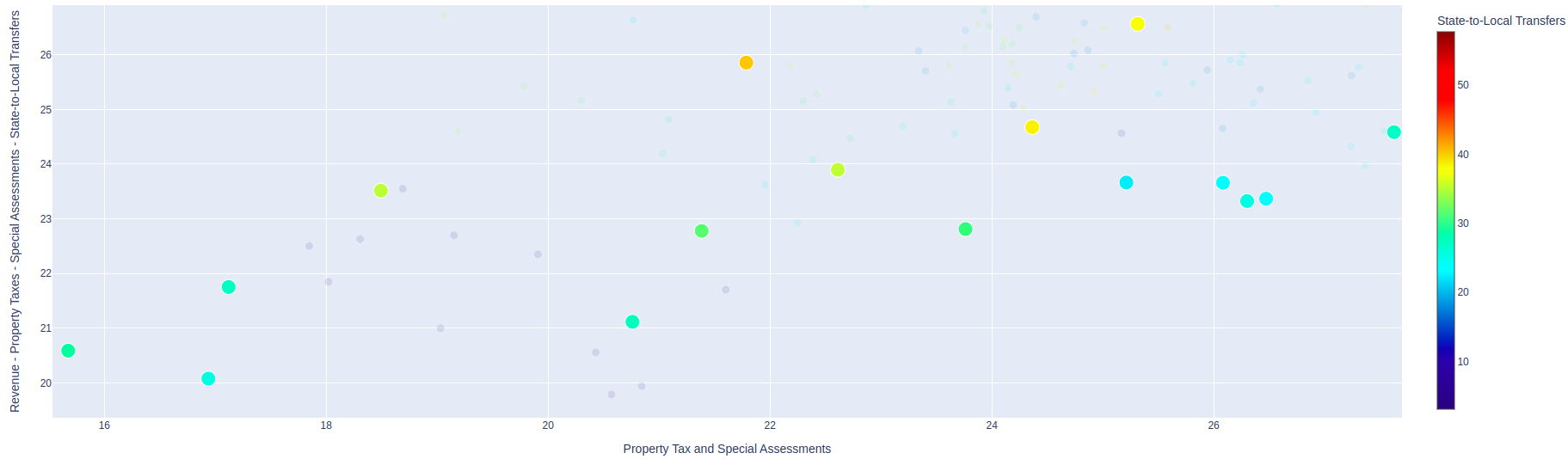

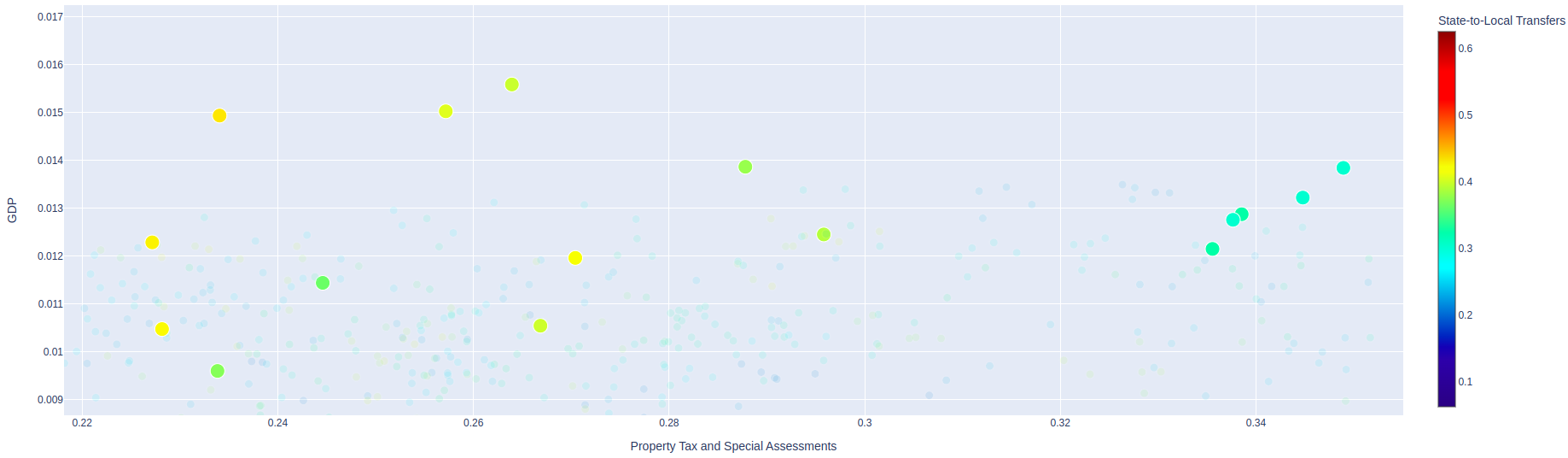

We are concerned specifically with the behavior of budgetary components in North Dakota. A careful look at the data reveals that when the budget is divided between 1) Property Taxes and Assessments, 2) State Transfers, and 3) remaining sources of local revenue, that a clear tradeoff emerges. Between 2005 and 2021, state-to-local transfers have compensated whenever property tax income growth did not keep up with GDP growth. In Figure 1, we see that, for a given value of property taxes and special assessments as a portion of GDP, state transfers increase as the remaining portion of the budget increases. Likewise, in Figure 2, we see that for a given level of property taxes per capita, state transfers per capita increase as the level of GDP per capita increases.

Format: Percent of General Revenue

Figure 1

Format: Per Capita Values

Figure 2

Revenues By Source (Proportion)

Figure 3

The patter reflected in the included figures should be no surprise since. Starting in 2009, the state has implemented property tax relief. Even as of 2024, a North Dakota resident "[h]omeowners with an approved application may receive up to a $500 credit against their 2024 property tax obligation." The state is directly offsetting property local tax obligations. Given the states willingness to offset local property taxes, one must expect that this pattern continues if property taxes are banned. Barring this, we can expect that a gap will be left uncompensated in local budgets. Either local governments become more dependent upon the state, they become unable to provide resources to their citizenry, or some combination of these. There is no neutral choice here. Either property taxes remain local and local sovereignty is maintained local revenues diminish and local governments become financially dependent upon higher levels of government. One's view of the significance and legitimacy of property taxes must be formed in light of the alternative outcomes that would manifest should property taxes be eliminated, whether in part or in whole.

Appendix¶

Data transformation does not include Population, Home Price Index

Relevant Sources:

Johns, J. and Bhat, M. 2024. North Dakota Considers Eliminating Property Taxes. Tax Foundation.

Foldvary, F. Geo-Rent: A Plea to Public Economists. Econ Journal Watch.